The Plaque and The Square

Words and photographs by Sandy Di Yu published in JoCP Memory, 2022

There’s a building at the University of London Goldsmiths campus donning a plaque that displays the following text:

TIANANMEN BUILDING

This building is named in memory of all those Students murdered in

Tiananmen Square on 3 - 4 June 1989

I took a photo of it back in 2017 and sent it to my mum one night after a disappointing few pints at the student lounge. In the haze of cheap beer and dusk, I was convinced that this tribute recognising an event that had surely impacted her would be well-received.

Her response surprised me. “Don’t trust everything from Western media.” My mum’s message glared at me from my phone screen, unintentionally resurfacing an identity crisis I forgot I had.

Stubbornly unresolved, this singular crisis has been made all the more complicated in the era of rising violent crimes against East Asians and populous sentiments that have xenophobia at its core. How is one to establish an identity in these conditions? Being an immigrant twice removed, how do I reconcile with my Chinese heritage in an era of palpable rising Sinophobia? And can I even do so whilst remaining critical of the injustices perpetrated by governing bodies, like what happened at Tiananmen Square in 1989?

But being critical of an event can take on entirely new meanings when working through the reticular complex of identity. Taking my mum’s words as a starting point, the questions then become, what did happen at Tiananmen Square, and what does this event mean?

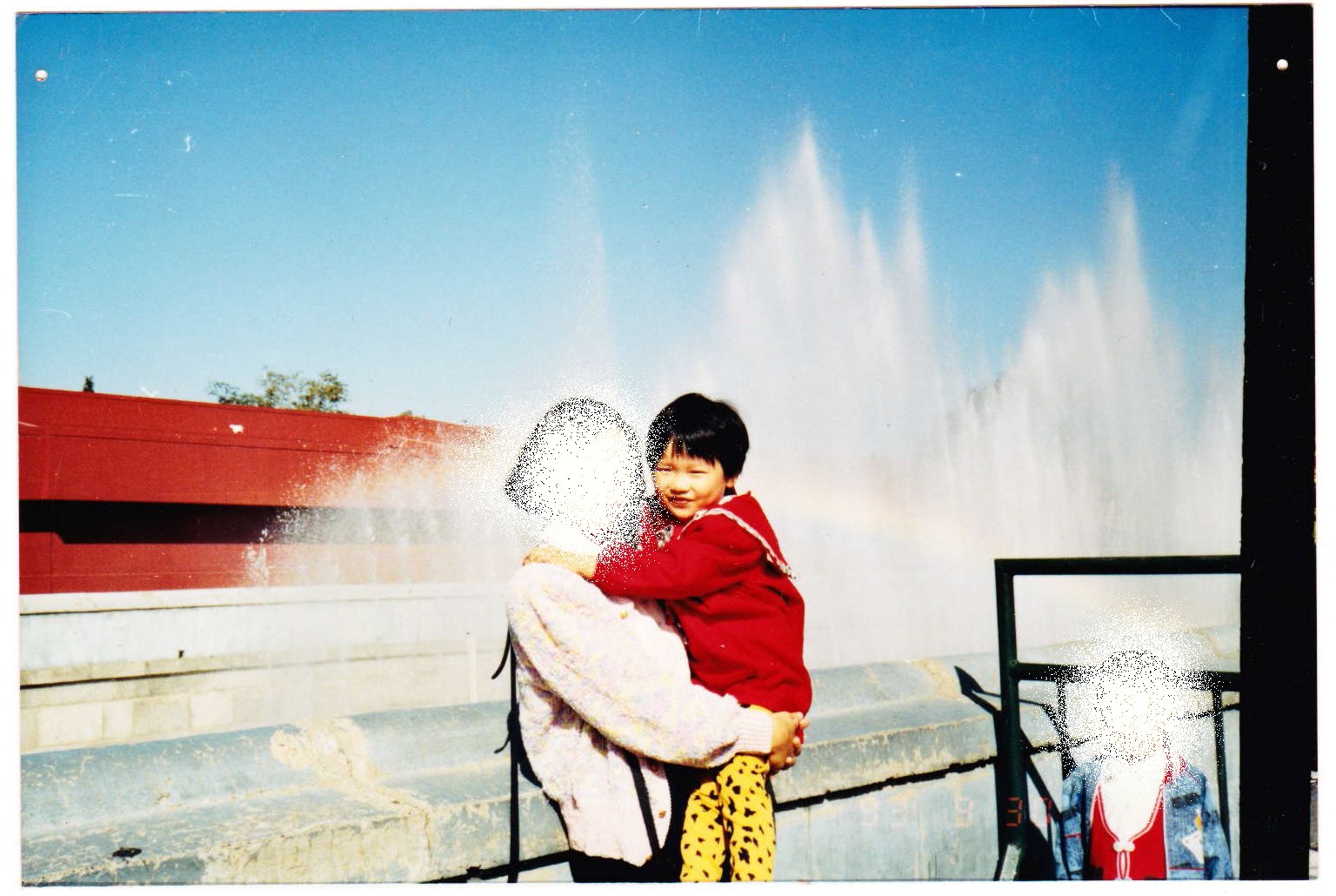

In the spring of 1989, my parents were living in Beijing as working professionals. My mum was pregnant with me. Protests were taking place in Beijing and throughout China. My dad joined in on the crowds for a day or two. By his retelling, he just wanted to see what the fuss was about.

Then, on June 4th, a militarized government caused the death of numerous civilians. Tiananmen Square suddenly became a symbol of protest, revolution, and ultimately, draconian disciplining.

My recollection of Tiananmen Square greatly contrasts with this symbolism. I remember the Square as a place of relentless sunshine and fireworks, of humid summer air and long flights to visit relatives both distant and close. I used to attribute to it the same importance that small children assign larger-than-life architecture, like the ones that you’d read about before seeing in person. The Square was also a place of teenaged frustration, of being unfathomably bored on a month-long trip back to China when I was seventeen and had much better things to do, like making my last-ever updates to Myspace and learning how to roll a joint. It’s a place that reminds me of being pissed off at my parents for suggesting that my high school boyfriend and I were probably not going to last (we didn’t), but also of relatives who spoiled me rotten with compliments and presents because they hadn’t seen me for so long.

For the rest of the Western world, the Square is a place where freedom is laid down to perish. The ‘official’, short and sweet version of the story, the one implied by the words on the plaque and told and retold by the Western media that my mother so disdained, was that students were protesting for democracy and freedom, and the authoritarian Chinese government murdered them for speaking up.

My mum was quick to tell me that it was more complicated than that. She didn’t elaborate at the time, but by my own research, there was indeed more to the story. It wasn’t just students; there were also labourers and workers’ unions of all sorts. And it wasn’t a fight for “freedom” in the platitudinal, neoliberal sense that places expression above a right to health, shelter, and security. Rather, it was for concrete demands to address inflation, corruption, and increased competition in the job market. Neither was it a clear-cut clash between students and the government. There was tension between students and workers, where the students initially disallowed common workers from joining in their campaign. It was in fact these workers, who were suddenly earning a living wage, that drove up inflation, and these workers, who were once secluded to the countryside who entered the job market. In many respects, the students weren’t fighting for freedom so much as exclusivity.

But people protesting were killed regardless, so why do these differences matter?

On the Goldsmiths campus, there’s also a building named after the pioneering cultural theorist Stuart Hall. That his name is seated next to an emphatically one-sided declaration about Tiananmen Square might be tinged with a vignette of irony.

For Hall, it is true that “communication is always linked with power and that those groups who wield power in a society influence what gets represented through the media.” Meaning is communicated and understood through shared cultural and societal maps, and meaning is never fixed because a level of distortion will always occur through its representation, which is contingent on the power dynamics of these societal maps.

Broadened to encompass the scale of cross-societal (read: colonial)power struggles, Hall’s analysis of representation applies just as fitfully. On some level, the right to represent these events is always a struggle between two world powers. What, then, can we assign as the meaning of the event that we might call “what happened at Tiananmen Square”?

We might look at what Hall says about Northern Ireland during the time of the Troubles. On the meaning of Northern Ireland, he says, “What is dubious is what the true meaning of it is, and the true meaning of it will depend on what meaning people make of it, and the meaning that they make of it depends on how it is represented. The meaning of an event in Northern Ireland does not exist until it has been represented, and that’s a very different process.”

Similarly, the meaning of what happened at Tiananmen Square does not exist until it has been represented, and it is in its very representation that meaning may be derived. And so, when represented by the plaque on that brick building at Goldsmiths, it has one distinct set of meanings, one that I find increasingly difficult to access when attempting to adopt an anti-imperialist lens. This is the same set of meanings that are derived from representations throughout Western media. That’s all fine, they would be remiss in consistency if this weren’t the case. But if we can conclude that these meanings are all from representation centring Western socio-political interests, then the possibility of an invariably alternative mode of representation through which such an event can be considered opens up.

The night I sent that photo to my mum, I went back to my shared flat and sat in the kitchen mulling over my unkempt thoughts. One of my roommates came in to make herself tea. She was born in China just as I was, but unlike me, it’s also where she grew up, thus where she called home. I was envious of how irrefutable her answer was when people ask where she’s from. When people ask me, I tell them I’m from Canada. It’s the only place I currently hold citizenship, whatever that’s worth. Sometimes, they press on. “No, but where are you really from?” Cue deepened identity crisis.

I asked her if she knew about the Tiananmen Building at Goldsmiths. As we spoke, another roommate came in who was also from China. The three of us recalled and discussed our memories of the event. Although it occurred before any of us were born, we each had distinct memories of it.