Thinking of Climate Change Through the Identity of Tharu Indigenous People

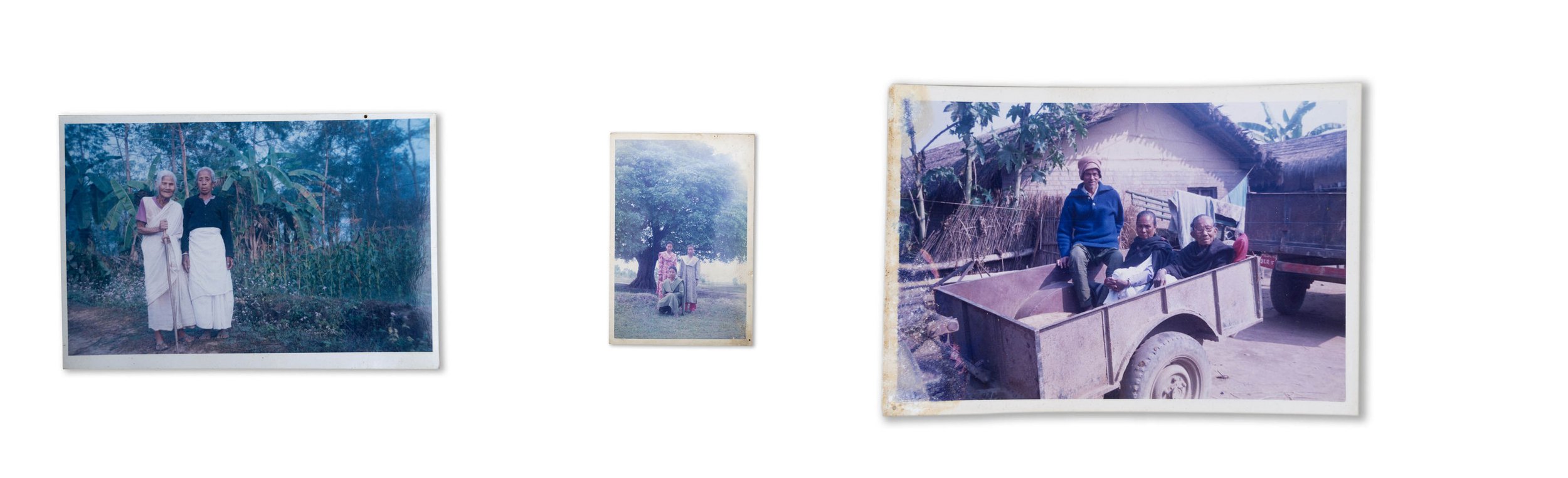

Nepal Picture Library (NPL) is a digital photo archive established in 2011. In the early days, it was the conversation around the lack of representation that made them question - “how can we use the visual medium to diversify the images we are seeing of the country?”, says Diwas Raja Kc, the exhibition curator at NPL, as he introduces the organisation to us. Based on this line of thinking, the visual practice of NPL at the time was directed towards the idea that history begins at home. They encouraged people to think about their family history and journey through personal albums to understand how they relate to the broader narratives surrounding the history of Nepal, which is exclusively representative of a particular class and gender. “So through this visual practice, we attempt to rectify the dominant narratives of history,” he explains. Therefore, NPL encouraged the wider public to submit personal photos “to see how much history was trapped in those albums and those private domains of people’s homes,” he continues.

Photo by Richard Pete Andrews-1968

As a group of mostly academic researchers, the visual medium allows them to break down barriers to communicate with the wider public to make their research accessible. As Yutsha Dahal, a research fellow at NPL explains, “Visual medium gives a different kind of access to the public and from the public to us. It breaks down barriers that come from a socio-economic background or educational history which disappears when you have a photo to which you are communicating with.”

As they progressed, they began to question the usefulness of this practice. Over time, they were overwhelmed by the large volume of materials sent to them. Therefore, in 2016, they switched gears and started thinking about building archives around social movements that are happening in the country. One of the products of this concept is an exhibition titled, ‘The Skin of Chitwan’. This exhibition “seeks to re-imagine conversations around indigeneity, change in climate and ways of life, traditional knowledge systems, ideas of development, progress and sustainability, and indigenous ideas of futurity,” NPL describes. It invites us to “imagine a future where it is not dominated by the mainstream Western idea. What kind of future do we imagine having when we are in this current climate situation? In that future, where is our place? Where is the place of indigenous people? Are they already forgotten? What is their role in that future that we imagined?”, Yutsha elaborates. To imagine this future, we are invited to think about our past. More specifically, questioning “how the experiences of Indigenous communities can be tools that we can use for our fight in the future?” Diwas adds. Central to this exploration is the identity of Tharu Indigenous people residing in Chitwan. Tharu Indigenous people comprise more than a million people who live in the Tarai region. Tharu of Chitwan is one of the many subgroups that reside in the centre of the Tarai region.

Due to the global pandemic, NPL has adapted their exhibition digitally which gives us a unique opportunity to be able to step into the exhibitions from thousands of miles away. As we enter the exhibition, it introduces the landscape as a witness to our past and as a medium that tells a story about the prospect of our future. The landscape carries with it the traces of life that came before which will shape and determine the future we are set to live. As we get caught up in the progress and development of today’s world, our landscape reminds us of what matters, and that is “the habitability of Earth,” the exhibition argues.

This exhibition is looking at the landscape of Chitwan through the lens of the Anthropocene. The word ‘Anthropocene’ has been used in this exhibition to “designate the present condition in which humanity's unmitigated ambitions are engineering the very conditions of life and death on Earth to the extent of penetrating the planet’s core geophysical dynamics,” the exhibition defines the term. It tells a story of how human ambitions for progress have deeply impacted the existence of Tharu Indigenous people and their life-sustaining relationships with the forest. Looking at Chitwan through the lens of Anthropocene, or more specifically, climate change is a rather risky concept for them to explore as the image of climate change in this region is not as dramatic as it is in other parts of Nepal. Diwas enlightens, “A lot of conversation around climate change in Nepal has happened around the mountainous region in the North of Nepal. Whereas, the conversations around environmental issues in the South haven’t focused much on climate change because the effects in the South aren’t as dramatic as what happens in the North.” With the lack of shock factor that the condition of the Southern region of Nepal (where Chitwan is located) presents, there was never any sense of urgency to talk about climate change in this region. But that is the idea of this exhibition. To bring to the surface and generate conversation around the hidden and more subtle narrative of climate change. The kind of change that we often overlooked until it escalated into an image that forces us to start paying attention. “We are toying with something invisible. The forms of violence happening in this region are not immediately felt and seen. The kind of disorientation that happened is not immediately palpable even to people who are experiencing it. Visually, it has to unfold gradually as opposed to the dramatic image of climate change,” Diwas explains. To assess the issue of climate change, this exhibition delves deeper into deforestation and the larger and deeper unseen histories they tell about the lives of the Tharu people. Tharu people have very strong economic, spiritual, and cultural attachments to the forest that largely shape and define their identity as Tharu Indigenous people. However, as this exhibition progressively shows, as the forest disappeared and transformed into Chitwan National Park, pieces of their identity disappeared along with it.

To show a subtle yet important part of the narrative of climate change in this area, on one occasion, this exhibition illustrates the connection between the Tharu people and the Simal trees of Jayamangala through a story told by a local. He reminisces,

““This is a Simal Tree, also known as cottonwood. This is the season when its flowers will blossom. The flowers leave fruit that contains white cotton-like fibres inside. In the past when cotton wasn’t available around here, local Tharus came inside the jungle to collect the fibres from Simal trees. They used it to stuff their pillows or blankets.””

However, in contrast to this image painted to us, we are witnessing images of the non-existent Simal trees on a burnt field instead. What follows the disappearance of the Simal trees from the forest is the disappearance of a small piece of Tharu’s lifestyle.

A larger and more impactful change to their life and their identity is the sanctity of the forest, or the lack thereof, for the Tharu people. “In the old days, the Tharu might be walking into the forest and would have an encounter with the divine or ghostly or some kind of force. Then, they will tell these stories to others. So there is a sense of respect and fear associated with going into the forest,” Diwas tells us. However, as the forest slowly disappears and the intrusion from the outsiders, many of their gods and the spirits that roam around in the forest disappear. They are losing their sacred connections with the for- est. However, this is not to say that they are losing their beliefs, as Yutsha clarifies, “They still believe in their gods and the spirits, but because of the outsiders who don’t have the same respect and fear towards their gods the same way they do, therefore, their gods have disappeared. So it is not that their beliefs have stopped, but because of the intrusion from the outsiders, their gods have been displaced, and so they have also been displaced.”

As a form of violence, the idea of displacement discussed in this exhibition is highlighted within an angle that is also hidden and subtle. It makes it difficult for us, and even for the people who are experiencing it, to realise that it is a form of violence. “When we say displacement, the story of Chitwan isn’t like other stories that Indigenous communities in different parts of the world have faced, which in most cases are far more violent. In the context of Chitwan, these Indigenous people continue to dwell in the places that their ancestors have inhabited. They haven’t been violently ejected from their land to settle elsewhere. They continue to live in that place, but just the place itself has been violently changed,” Diwas clarifies. Due to this subtle and invisible form of displacement, Chitwan hasn’t witnessed the kind of spectacular protest, struggle, or revolutionary movements that have happened in other regions. “Displacement in the context of the Tharu people residing in Chitwan is shown as a compromise that one must make for the sake of progress, which is why it was difficult to recognise this as violence,” Yutsha explains. When talking about progress, one must wonder, at whose cost? Why do some groups or communities have to sacrifice a lot more for progress than others? Why are some groups more vulnerable to being subjected to this compromise? Are they actively involved in this conversation around progress and the compromises they have to make? Are those who sacrifice the most will in any shape or form benefit from this progress? Problematically, those who have to sacrifice the most are those who are the least consulted with any of the changes they have to endure. These changes are merely imposed on them and they are expected to conform to them and, in some cases, forced to conform to these changes. In the case of the Tharu people, their needs are ill-considered compared to the larger needs of progress and development initiated by the elites and those who are in power.

With the lack of conversation being had about the existence and preservation of Tharu Indigenous people and their customs and beliefs in the present time, we are moving towards a future where this group of people will no longer exist. As this exhibition argues, “the erasure of Tharu people from the flow of time means they need not be consulted for decisions about the present and contemporary life, nor about the future. And the people who are absent in the future can be destroyed in the present along with their habitats and ecologies.” Therefore, as we scroll through this exhibition, we are observing the disappearance of the forest and not too far behind is the disappearance of the identity of the Tharu Indigenous people. Eventually, we are ensuring their absence in the future that we imagine.

To visit the virtual exhibition: skinofchitwan.nepalpicturelibrary.org

Courtesy of Mangani Raut